Saving Labor, Also Safeguards Labor

If any place in America ought to have manufacturing jobs, it should be a place with a name like “Steelville” The brothers Dennis, John and Robert Bell all agree.

In Missouri, the muscular name Steelville actually refers to a rather small town. This town is home to 1,400. It is also the home of the contract machining business the Bells have owned since the 1970s, the Steelville Manufacturing Company. Last year, this company saw a rate of employment growth that few companies in any industry, let alone manufacturing, could have boasted. At the end of 2008, Steelville Manufacturing had 80 employees. By the end of 2009, the number had passed 100.

How the company found the confidence to commit to this expanded workforce might strike many as counter intuitive. Specifically, the company increased its commitment to automation. It added machining centers that are fed by a pallet system instead of standing alone.

Typically, automation is seen as an alternative to labor—and from the standpoint of how any particular job will run, that’s precisely what it is.

However, from the standpoint of how a manufacturing business will expand, automation is a safeguard to labor—because automation is the better answer to volatility. In the case of Steelville, the company is now more free to expand, without making its growing workforce excessively vulnerable to business fluctuations, thanks in part to the way that automation offers unattended capacity for absorbing surges in demand. Thus, the company can staff for a conservative level of business, but pursue a level of business that is much higher.

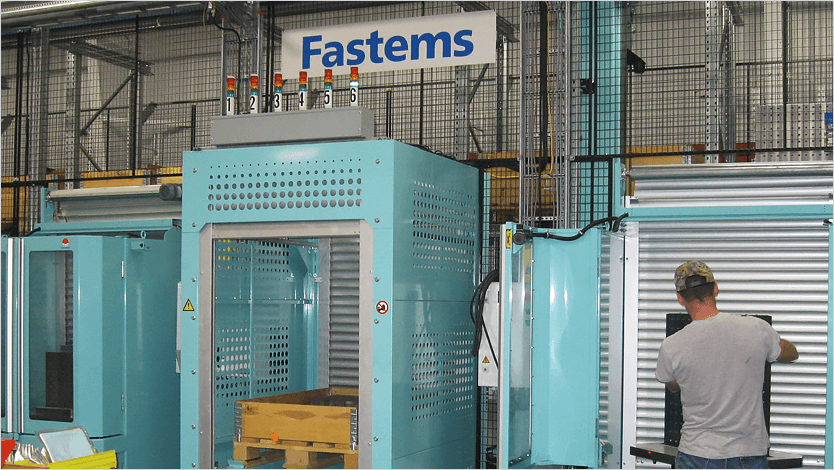

Steelville’s newest asset for absorbing these surges is a cell built around a Fastems pallet system—one of the longest installed systems from this supplier in North America. Fastems supplies multi-level pallet storage and retrieval units that link separate, standalone machining centers (even machines from various manufacturers) into unified cells. At Steelville, the system has 52 fixture plate places and 42 material pallet places, with the 162-foot length of the cell providing space enough for at least six large horizontal machining centers in addition to the various load/unload stations.

Four of those machining centers are now in place. They include two five-axis machines with 800-mm pallets and two four-axis machines with 630-mm pallets, all from Okuma. The machines all share pallets interchangeably, despite the difference in pallet size.

Now, the cell created by uniting the four machines in this way serves as the “large part” cell in Steelville’s facility. It runs in parallel with an existing pallet cell for smaller parts that was purchased as a complete, integrated system from a machining center manufacturer. Even though the shop did not want a single-company system for its second cell, its understanding of just how much value a pallet cell can deliver has come from watching what this first cell for the company has been able to do.

Steelville vice president John Bell says that installing a pallet cell is, of course, more expensive than installing just standalone machines. Emotionally, the cost might be hard to justify. The pallet unit itself doesn’t make chips.

However, he says the extra cost alone is not the important point. Rather, the important point is that the break-even threshold for the pallet system does not require the shop to capture round-the-clock production—or even anything close to that. As a result, some of the capacity created by the cell is, in a sense, free for the taking. That’s because the shop doesn’t have to fill all this potential. It doesn’t have to staff for that level of work, either. Instead, the shop staffs for the low end of expected demand, while the pallet system makes it possible to run long, unattended, overnight shifts whenever extra capacity is needed. Thanks to automation, much of the shop’s potential capability is optional, in terms of its impact on whether the company’s staffing needs to rise or fall.

If you build it

If you build it

Steelville makes aircraft parts, machining aluminum, titanium and steel. The shop’s machining centers produce plenty of geometrically challenging components. However, the shop has cultivated a reputation as a reliable, cost-effective source for simpler and less glamorous parts as well. Mr. Bell jokes that the company hopes to go after the work left behind by other shops pursuing 787-related machining.

He says a “Field of Dreams” approach drove the purchase of the new cell. There was no particular job or set of jobs that justified the complete system, let alone any of the machining centers by themselves. Instead, the shop built the cell, and (fortunately) the work did come. More accurately, distributor Hartwig Inc. built the cell for Steelville, with Hartwig’s Missouri office supplying the machines, the Fastems system, and the various integration and engineering services involved in tailoring and installing the completed cell.

The long Fastems unit itself is essentially a pallet cell missing only the machining centers. Two levels of storage hold pallets that Steelville has dedicated with fixturing for particular job numbers. The unit’s pallet retrieval system delivers pallets to load/unload stations for operators, or to the machining centers themselves according to the scheduling of the system’s cell controller.

Pallets transfer to the machines on fork-like lifters, not on fixed and dedicated rails. That means there is no “hard” connection between the machines and pallet storage. Steelville can therefore add or replace machining centers as it chooses, freely changing the number, sizes and models of the machines in the cell. This freedom is precisely what made the third-party approach appealing for this latest cell.

“We’ll still be here in 20 years,” Mr. Bell says. The earlier, single-source machining cell continues to serve the company well, but the shop wanted its next cell to be free to adapt to whatever changes in capacity prove to be important in the years to come. With this new cell, the shop isn’t locked into any machine size, type or supplier. The machining centers might change, but the pallet cell approach seems here to stay.

Why Cells Make Sense

The reason the pallet cell approach is valuable became apparent to the shop practically within weeks of first realizing the value of HMCs. Until 2000, all of Steelville’s machining centers were verticals. The shop was convinced of the benefits of the horizontal configuration well before it finally committed to this change. Once it did, the shop was quick to discover just where the productivity limits of those initial HMCs were to be found. Jobs would be set up on a standalone HMC’s two pallets according to carefully scheduled production runs, but customers with emergency orders for small quantities would then require both the schedule and the setups to be reworked in haste. Only a solution like a pallet cell could allow a large number of jobs to stay in place on dedicated pallets, so that setups could move in and out of the machines in time with unplanned customer demand.

In fact, Mr. Bell says these sorts of short runs are what make a cell truly productive. Some shops tend to assume that cells make the most sense for high-volume production, but he finds the opposite to be true. If long production runs are needed, then stand-alone machines are fine—the operator loads and unloads pieces at one pallet while the second pallet is in the machine. When the setup has to change is when the spindle utilization of a standalone machine tends to suffer. By contrast, a machine fed from a pallet system can keep spindle utilization high, because a series of jobs on a series of pallets can be run throughout all the time that might be required for one of the pallets to receive some lengthy new setup.

+26% Value

Advantages like this actually make employees’ efforts more valuable—even during daylight hours. In fact, Steelville has measured this value increase. Using a pallet system in place of standalone machining centers allows each machining center operator to deliver 26 percent greater value, the company says. This increase in value is partly because the cell approach permits a larger ratio of machining centers to operators. Another part of the increase comes from the increased production that results from emergency orders being filled without interrupting a machine’s cutting. This increase in employee value is yet another part of the payback that the company realizes from pallet cell automation, Mr. Bell says—and this part of the payback doesn’t even take the lights-out capacity into account.

Written by Peter Zelinski

Originally appeared in Modern Machine Shop magazine, copyright 2010, Gardner Publications Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio.

Related products:

"*" indicates required fields